A new report finds that deepfake software is still prohibitively hard to use, but that may not be true for much longer

A comparison of an original and deepfake video of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

IMAGES: ELYSE SAMUELS/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES

If you wanted to make a deepfake video right now, where would you start? Today, an Amsterdam-based startup has published an audit of all the online resources that exist to help you make your own deepfakes. And its authors say it’s a first step in the quest to fight the people doing so. In weeding through software repositories and deepfake tools, they found some unexpected trends—and verified a few things that experts have long suspected.

The deepfake apocalypse has been lurking just over the horizon since about 2017. That’s the year the term was invented by the eponymous reddit user “u/deepfakes,” who weaponized the face-swapping technology to graft famous actresses into porn.

Fears of other kinds of misuse quickly spread: In the two years since, U.S. Congressional panels have convened to assess whether faked video scandals will undermine democracy. Apps have popped up that use deepfake methods to turn any photo of a fully-clothed woman into a naked snapshot. There have been reports of fraud and identity theft abetted by deepfakes.

And yet, so far rumors have largely outpaced actual deployment. To be sure, nonconsensual pornographic videos are a scourge. But deepfakes have not spread beyond these boundaries. Politics is dogged more often by “cheapfakes” and “shallowfakes,” low-tech media manipulations best characterized by the infamous video of U.S. house majority leader Nancy Pelosi slowed down to make her look unwell or drunk.

“The apocalypse is a little overhyped in my view,” says Siddharth Garg, a researcher at New York University.

If you wanted to make a deepfake video right now, where would you start? Today, an Amsterdam-based startup has published an audit of all the online resources that exist to help you make your own deepfakes. And its authors say it’s a first step in the quest to fight the people doing so. In weeding through software repositories and deepfake tools, they found some unexpected trends—and verified a few things that experts have long suspected.

The deepfake apocalypse has been lurking just over the horizon since about 2017. That’s the year the term was invented by the eponymous reddit user “u/deepfakes,” who weaponized the face-swapping technology to graft famous actresses into porn.

Fears of other kinds of misuse quickly spread: In the two years since, U.S. Congressional panels have convened to assess whether faked video scandals will undermine democracy. Apps have popped up that use deepfake methods to turn any photo of a fully-clothed woman into a naked snapshot. There have been reports of fraud and identity theft abetted by deepfakes.

And yet, so far rumors have largely outpaced actual deployment. To be sure, nonconsensual pornographic videos are a scourge. But deepfakes have not spread beyond these boundaries. Politics is dogged more often by “cheapfakes” and “shallowfakes,” low-tech media manipulations best characterized by the infamous video of U.S. house majority leader Nancy Pelosi slowed down to make her look unwell or drunk.

“The apocalypse is a little overhyped in my view,” says Siddharth Garg, a researcher at New York University.

So—is a true crisis coming, and if so, when? The new report, issued today by the counter-deepfake firm Deeptrace, based in Amsterdam, tries to answer those questions. Deeptrace is one of several new startups and academic groups that aim to build ”deepfake detectors” to guard against the coming storm of AI-generated content. But the company’s employees realized they first needed to better understand what exactly is out there. So they conducted the first major audit of the deepfake environment on the open web.

Most media coverage of deepfakes has focused on the highly realistic, seamless videos produced by leading academic labs. Deeptrace wasn’t interested in those, because the researchers who create them keep the underlying code under lock and key. “We never publish any of our code,” says Siwei Lyu, a digital forensics researcher at the State University of New York at Buffalo. “It’s too dangerous.”

So if someone wants to make a deepfake—for porn, extortion, or political hijinks—he (or she) must find the means to do so on the open web. Deeptrace wanted to know exactly what tools one might find there. Head of Research Henry Ajder and his team ran scraping APIs and other methods on a panoply of sites that included reddit, 4chan, 8chan, voat, and many others to quantify how many deepfake services were available, and how many videos had been generated with them.

The code on which most of the world’s amateur deepfakes runs can be found in eight repositories on the open-source code sharing and publishing service Github. (It’s all a version of u/deepfakes’ original code.) These repositories appear to be very popular, says Ajder, judging by the number of Github stars—a star is Github’s version of a favorite or like—which were comparable with some commercial software. The two most popular repositories had more than 25,000 stars between them.

This code is quite hard for the average person to use, though, and requires a great deal of data, tweaking, and time, which scares off most amateurs. But they have other options: on 20 deepfake creation communities and forums, Ajder and his colleagues found links to a small number of apps and services someone could use instead. These ranged in accessibility—some were cheap, most required around 250 images of the “target” to train the network. Ajder did not check the quality of the apps’ output but notes that all the deepfake porn websites have advertising, which implies the results are profitable.

Thanks to this small but proliferating set of sites and services, the number of deepfake videos on the Internet doubled between December 2018 and July 2019. But one thing stayed the same: 96 percent were pornographic.

IMAGE: DEEPTRACE

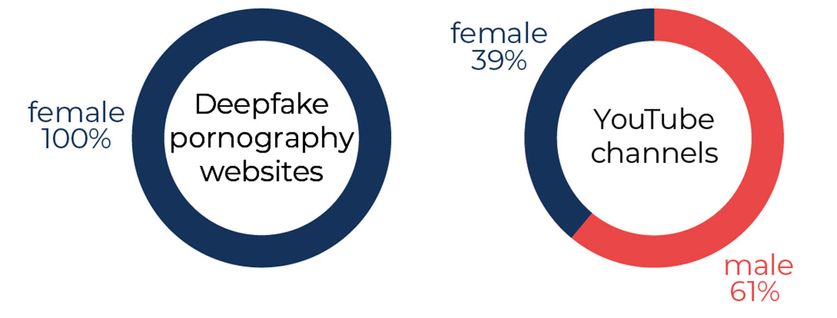

Fully 100 percent of pornographic videos the group found were of women (women were the subjects of 39 percent of non-pornographic deepfake YouTube videos analyzed by the group). “We didn’t find a single deepfake pornographic video of a man,” says Ajder. This has a lot to do with the milieu in which today’s deepfakes are created and peddled—on the 8chan and voat forums from which these services are linked, the locals might not take kindly to a person requesting pornography that strayed from their expectations.

Ajder admits that their data had some limitations. For one thing, they largely skipped the dark web. “It’s just such a deep dark hole and that makes it very difficult to explicitly search for deepfakes,” says Ajder. They also didn’t venture much beyond the English-speaking Western Internet, though there is evidence to suggest a lot of consumers of deepfakes come from South Korea.

Hany Farid, a synthetic content expert at the University of California Berkeley says that while there isn’t much in the report that will surprise experts, “there’s a lot of value in trying to understand the deepfake landscape.” Lyu says the report compiles many facts of which researchers have been aware—which is useful for lawmakers.

“If you want to inform policy makers and legal analysis of how to address this problem, it’s important to know what deepfakes are being used for,” says Garg, who is investigating similar issues at New York University.

“It’s also useful to see that what’s out there right now is mostly face-swaps,” says Lyu. “That limits the damage to a certain extent.” That’s because face swaps—grafting one person’s face onto another person’s head and body—are still unconvincing. Believing that such a video is real requires voluntary suspension of disbelief, says Garg—which is in plentiful supply for people watching pornography.

So: the code out there right now is hard to use and doesn’t make anything convincing except for porn. No reason to worry? Not so fast, says Lyu. The danger will come when deepfakes move from face swaps to body swaps. This kind of “puppet master” deepfake will hijack people’s entire bodies and animate them according to the desires of the coder. Lyu and other investigators have already developed code capable of doing this.

Deeptrace’s report devotes an entire section to generative adversarial networks (GANs), suggesting they will pave the road to these more sophisticated deepfakes. That’s in keeping with several recent releases of deepfake datasets by academic researchers to accelerate the development of deepfake detectors. But Lyu isn’t sure the focus should be exclusively on GANs. His method, for one, uses a different kind of encoder.

However, all agree that, one way or another, body swaps will be commodified sooner or later. And so, while they agree that the Deeptrace report is a good start to keep tabs on what’s available online, both Lyu and Garg say the next step should be a university-led, peer reviewed effort rather than one funded by private companies. “This would be a good project for the National Science Foundation to fund,” says Lyu.